Hacking Your Greeks: A Guide for Retail Options Traders

27 Apr 2025The market maker vs the path-independent options trader

There’s a common school of thought which views options as discrete, static bets. Check out Reddit’s wallstreetbets community for plenty of examples where a degenerate gambler buys 0DTE options and holds them to expiry; if they expire in the money then he celebrates his newfound riches, and if not then he loses everything. I wouldn’t say it’s wrong per se to view options like this, after all, the payoff of a vanilla option is mathematically

\[\max(S-K,0)\]But there are several shortcomings with this worldview:

- You’re not obligated to hold positions to expiry, you can close them in between.

- If you have dozens or hundreds of positions, are you really going to keep track of them in your head as discrete probabilistic bets?

- If we put on dynamic delta hedges, how does this affect our realized profits?

The point of this article is to introduce the market maker’s worldview of options, where we do not care to understand each individual option position, only high level summary statistics known as greeks. We realize that hedges are dynamic, risks are shifting in realtime, and the path that the option takes matters, not just the value at expiry. Even if you only wish to have static options positions open, understanding this worldview can unlock many interesting ideas.

Greeks as a low dimensional summary

The greeks are a good way to get into the path-dependent mindset because they are changing all the time: every time a clock ticks or the underlying price updates, the greeks will also update. Portfolio management becomes about trying to tame the wild fluctuations of the greeks in a way that is consistent with the trade you wish to express. I won’t cover the basics here, I assume you are already familiar with the most common greeks: delta, gamma, theta, vega, and rho. Instead, I want to show you some modifications you can make to the standard greeks to make them more reliable in practice.

Path dependence and mark-to-market

There’s this hilarious (but educational) article by Cliff Asness titled “My Top 10 Peeves”.

Many advisers and investors say things like, “You should own bonds directly, not bond funds, because bond funds can fall in value but you can always hold a bond to maturity and get your money back.” Let me try to be polite: Those who say this belong in one of Dante’s circles at about three and a half (between gluttony and greed).

Options, and any financial instrument in general, are the same. Unrealized losses are real! Mark to market valuations do matter! There are many reasons why they matter, but perhaps one of the most relevant is that your margin requirements are a function of the mark to market value of the instruments. Try explaining to your broker how you “only have paper losses, not real losses”. Once you internalize this you can identify why the following common statements are dangerous and wrong:

- Sell calls at a strike really far away, because the price of the stock will never get there. Then you have a steady stream of income by selling calls.

- A variation: buy 1 at-the-money call, sell 5 really far out-of-the-money calls to net out the premium. This gives you a “free bet” on the upside of the stock.

- Instead of placing a limit order to buy a stock when it dips, I’ll sell a put at a strike I’m happy to own the stock at. I’m getting paid to place a limit order!

- I always win by selling puts, because if the stock reaches a point near my strike, I can “roll” the option to a lower strike with a further expiry. This way I never actually realize the loss.

Once you can understand why all of the above statements are wrong, you are ready to move on to the rest of the article.

The most influential table on greeks

This one table, reproduced below, that has had the most influence on my trading has been from Nassim Taleb’s book “Dynamic Hedging”. Not much has changed since 1997 when the book was first published. The table is titled “Greeks and their shortcomings”.

| Greek | Definition | Shortcomings | Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | Sensitivity of a derivative’s price to the underlying security. | • Continuous-time hedging is purely theoretical. • Breaks down for portfolios that mix longs and shorts. • On its own, delta is an extremely weak risk measure. |

Use discrete delta hedging increments. Shadow delta blends in vega and gamma exposures for a fuller risk view. |

| Gamma | Rate of change (curvature) in delta. | • Portfolio-level gamma can be meaningless. • Ignores volatility changes that accompany price moves. |

Work with discrete increments. Track separate up-gamma and down-gamma values. Shadow gamma adjusts for the smile; skew gamma captures nonlinear vol shifts between up- and down-moves. |

| Theta | Sensitivity of an options portfolio to the passage of time. | • Misses how vol evolves as expiry shortens. • Ignores that vol often drops when markets are quiet. |

Reprice one day forward with a term-structure of volatilities (when vols are expected to converge). Use shadow theta to accelerate decay in calm markets and slow it in turbulent ones. |

| Vega | Sensitivity of an option’s value to changes in volatility. | • Misleading for calendar-spread portfolios—different maturities have different vol-of-vol. | Apply a volatility-curve model for weighting; advanced: use a covariance matrix across maturity buckets. |

Takeaway: none of the greeks exist in isolation!

Throw away the academic texts which produce lines upon lines of partial derivatives to explain the greeks. None of that matters in practice. The real takeaway is that all of the greeks are interdependent on each other. Easy example: let’s say tomorrow the SPX drops 10%. Our delta number that we computed is meaningless if we assume that the IV will stay static. It’s much more reasonable to assume that IV will jump from current number -> much higher number. We should use this more reasonable IV to compute delta, gamma, etc. The second takeaway is that the greeks are partial derivatives, and are therefore a localized number. They only explain what happens on an infinitesimal shift, not a large jump. In all cases, it’s more accurate to compute your greeks assuming a 1 standard deviation move to the upside or downside. I use a daily standard deviation equal to

\[IV * \frac{1}{\sqrt{252}}\]but you can scale the move according to your desired hedging frequency.

Guide to modifying your greeks

Delta

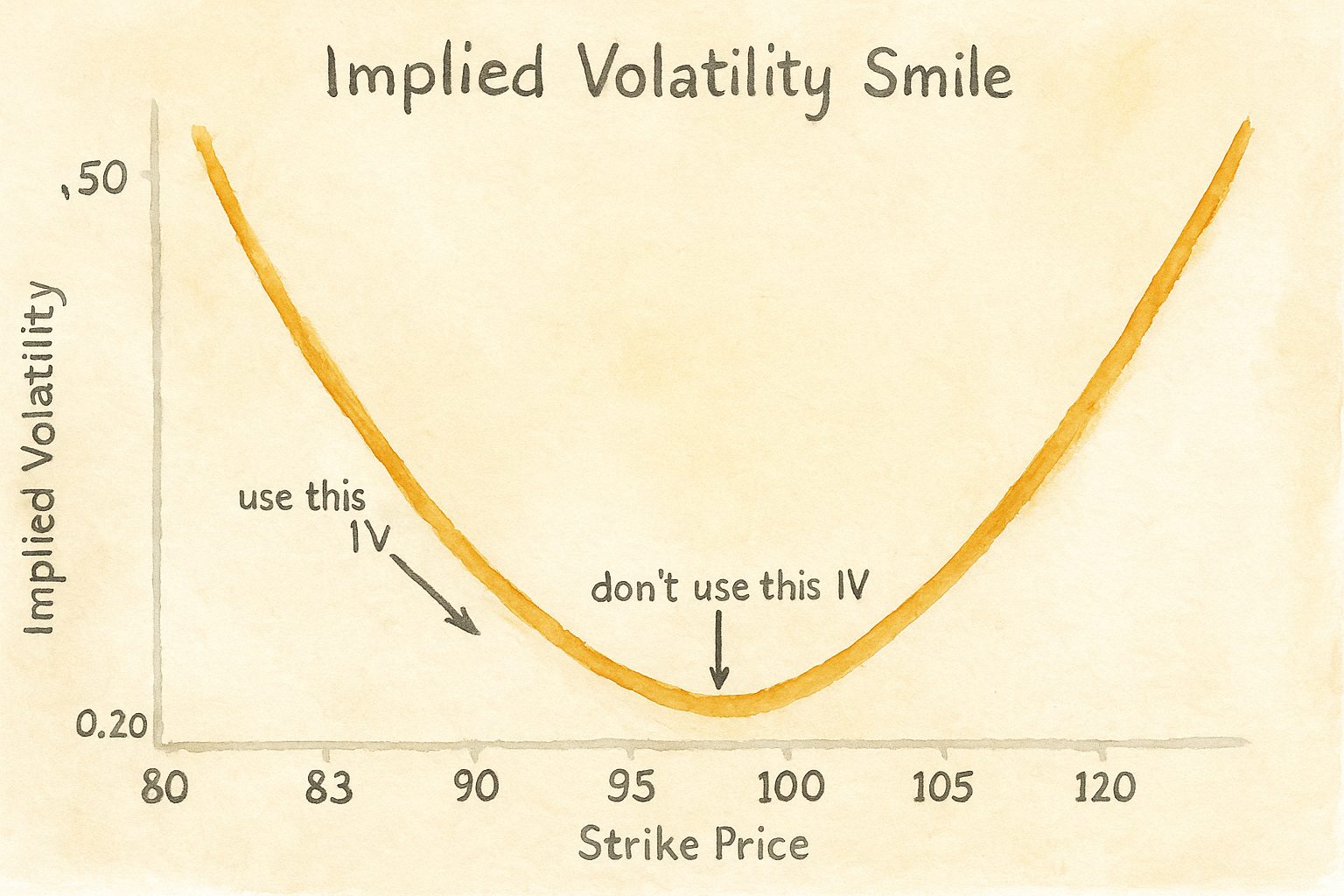

Assuming you are trading vanilla options, the delta is decently well behaved. Shift your underlying price up by 1 standard deviation and compute the delta, using the IV implied by the volatility smile. Then shift your price down by 1 standard deviation and compute the delta, using the IV implied by the volatility smile. Average the two to get your modified delta.

Gamma

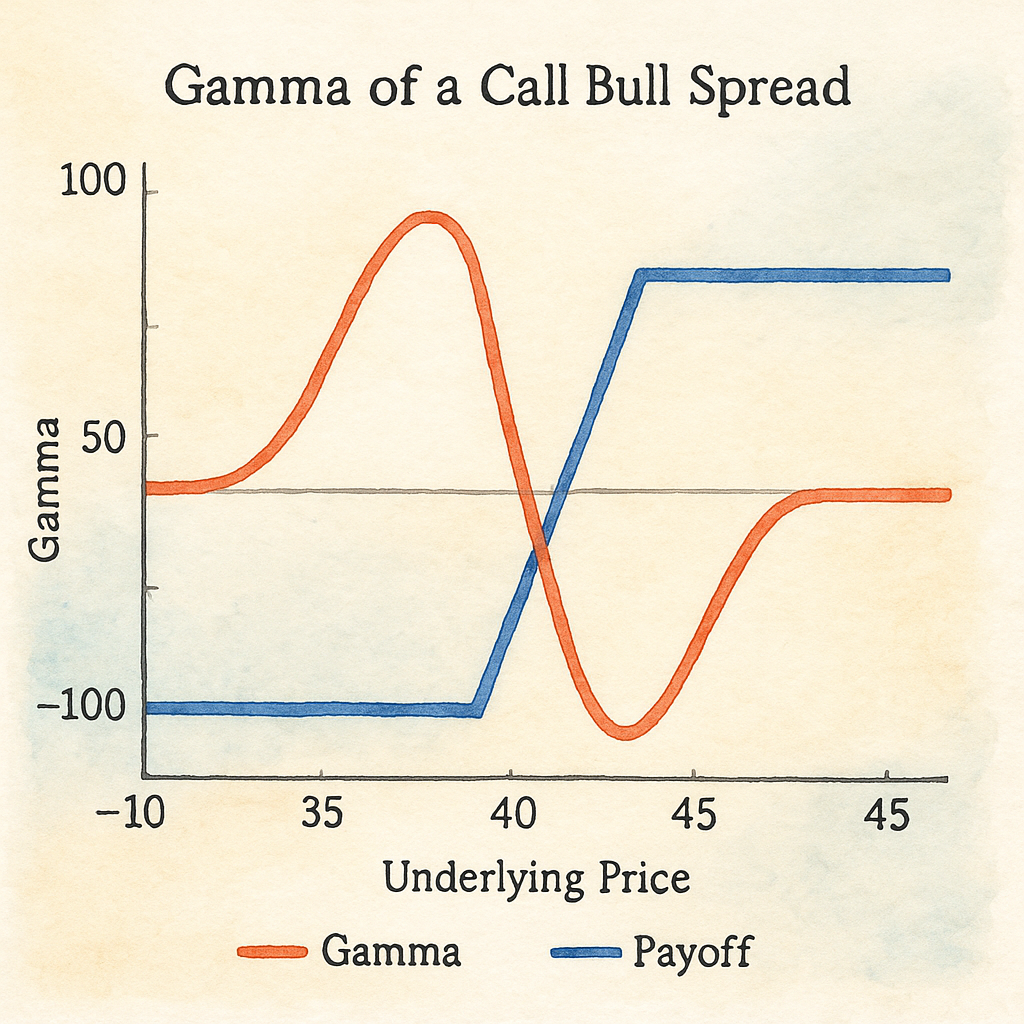

Remember that the gamma is an extremely unstable local measure. As the price moves, it’s very common that your gamma can go from positive to negative, or vice versa, (for example, in a call spread). Separate your gamma into two different metrics: up-gamma and down-gamma. For the up-gamma, compute the gamma on a 1 standard deviation move up of the underlying, making sure to use the new IV implied by the volatility smile. Repeat the same for down-gamma.

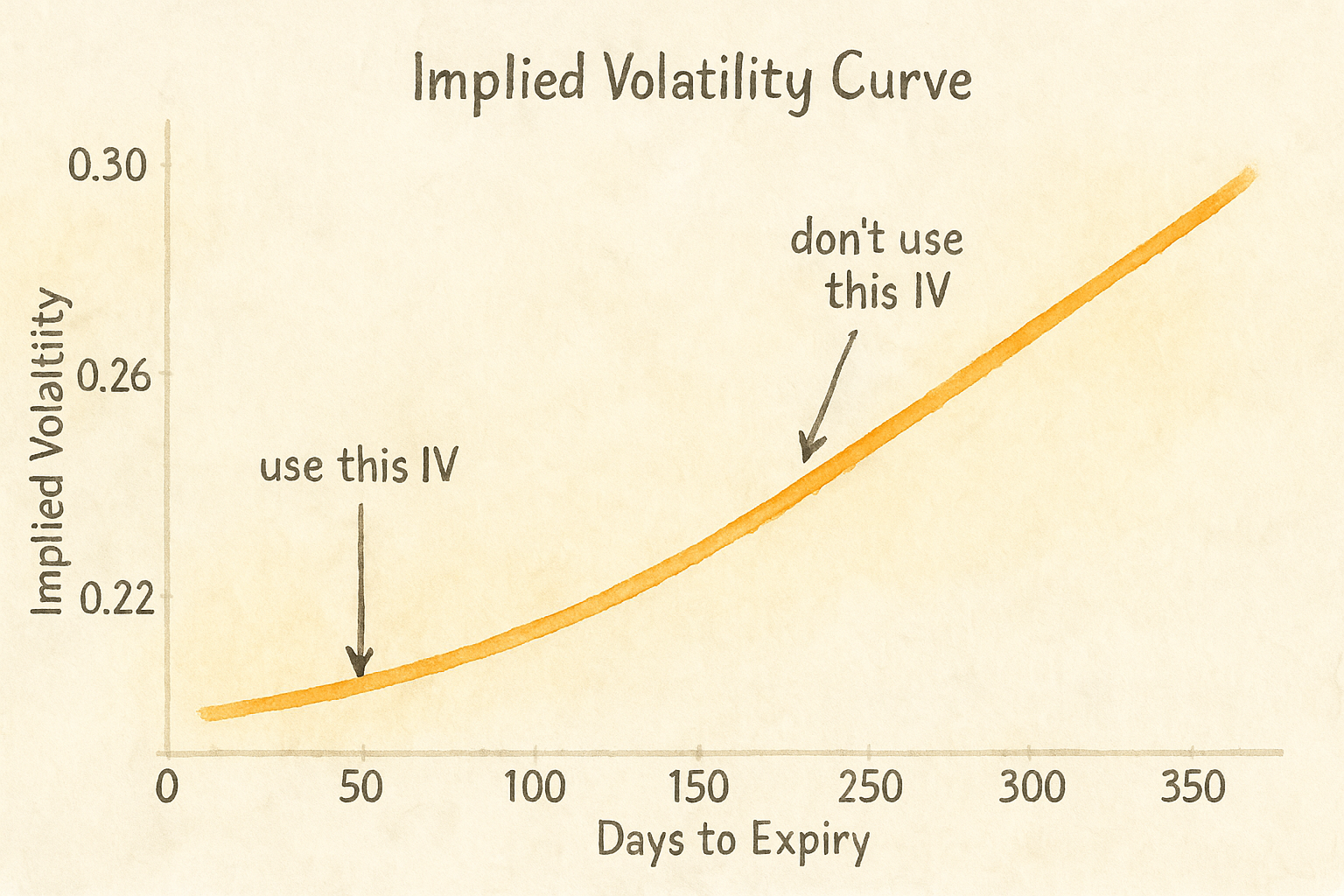

Theta

The main problem with theta is that if one day passes, we can’t assume the IV will stay static. We could be moving up or down the volatility term structure depending on if it’s in contango or backwardation. So compute the theta by shifting the expiration forward one day, and using the new IV implied by the volatility term structure.

Vega

Speaking of the volatility term structure, it’s well-known that the front of the curve is much more sensitive and will move with much greater magnitude than the back of the curve. Comparing raw vegas across two options with different expiries is useless, because it assumes the curve will shift in a parallel manner up or down. Instead, we can use an approximation that it follows a $1 / \sqrt T$ scaling factor. The time-weighted vega is benchmarked to, for example, a 90-day expiry:

\[\text{time-weighted vega} = \text{vega} * \sqrt{\frac{90}{T}}\]Bonus: delta and gamma bleed

Your deltas and gammas are changing as time passes. Recompute your delta and gamma by time-stepping forward 1 day, and take the difference between the forward value and the present value. This represents your “bleed”, or how much your deltas and gammas will change in 1 day.

Conclusion

- View your portfolio in terms of greeks, not static bets

- Greeks and mark-to-market values are changing all the time. These are real!

- Greeks unfortunately have many many pitfalls when using them to summarize a portfolio. The hacks here make them more reliable, but one could write an entire book about unexpected behaviors and nasty 3rd and 4th order effects that may affect your portfolio.